Almost every genre from RTS games, survival games, city-builder games, and so forth tend to gloss over an inconvenient truth about Western medieval settings: cast iron hasn’t been invented yet…

Unless this timeframe was the mid-16th century, the way we build stuff in-game out of iron ingots (like using a few hundred bars to make a statue) makes zero sense. The way we smelt iron ore doesn’t make sense either. And the scale of logistics, pricing, and scope of metalworking is a bit off as well.

But I’ll make this post to delve into the details of what’s missing and let the reader decide how much of it would benefit the game.

1). The Seven Metals of Antiquity

So a very abridged story of early human history is that humans discovered copper tools. They eventually discovered how to make bronze using arsenic and later a much less toxic process with tin alloys. Iron was seen as a nuisance whose presence would ruin a good batch of copper and would result in a spongy waste product. For geological reasons tin and copper tend to not be located in the same region, so advanced trade networks formed. Then the bronze age collapse happened in the 12th century BC. With international trade breaking down, societies were desperate enough to give iron-working (an otherwise useless waste product at the time) a chance.

Iron has a melting point of 1538°C (2800°F ). Compared to the other seven metals of known antiquity: Copper: 1084°C, Gold: 1064°C, Silver: 962°C, Lead: 327 C, Tin: 232°C, Mercury: -38.9°C, we can see that iron is a lot more difficult to process than the other known metals at the time. Using a typical smelter suitable for other metals would result in an unusable product. New techniques had to be developed to process it.

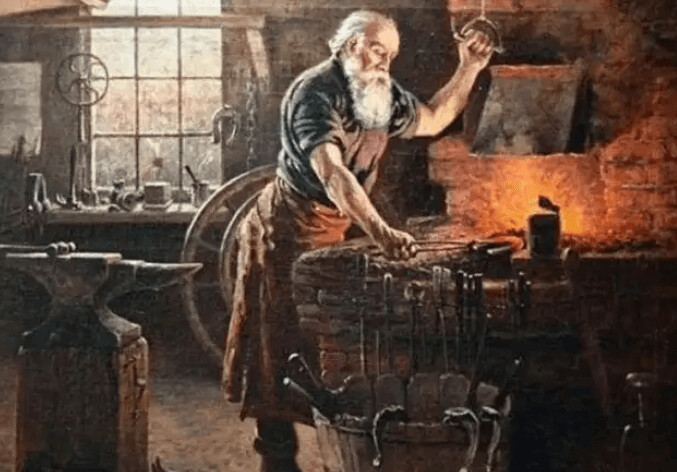

Moreover, we need to make a distinction between “Casting” and “Forging” metal. Copper (for certain applications), bronze, and the other metals mentioned above can be easily melted down into liquid form and poured into a wax mold of a desired shape and left to cool. This casting process can be easily used to mass produce objects like large pots, statues, plating, church bells, etc. The high melting point of iron is far unobtainable with available technology. At best, a small chunk of iron could be heated until it was soft and then gradually hammered into shape. This wrought iron is what you might envision at a blacksmith who makes a lot of small objects like chain links, nails, horseshoes, a sword, etc. at an excruciatingly slow pace.

Needless to say, despite wrought iron not being well-suited for economies of scale, iron is extremely abundant compared to copper (iron is the 4th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust), and wrought iron as a material is far stronger than contemporary bronze at the time. Given the scarcity of other materials, it was well worth the huge trouble, time, and resource investment.

2). The Bloomery Process

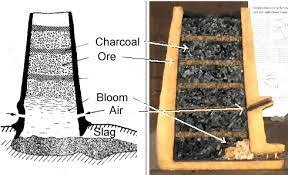

Through a lot of excruciating trial and error over the centuries, iron smelting became a lot more reliable as a process. Conspicuously absent in-game is a representation of the bloomery process:

With a little bit of clay, time, and a lot of charcoal, we ought to be able to make a disposable furnace very early-on in-game that produces small amounts of wrought iron (and if lucky, a bit of steel too). The chemistry behind what goes in a bloomery would take pages and pages to cover, but if you want to read up on it, I highly recommend this academic source that’s easy to understand:

https://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/iss/kap_a/illustr/ia_2_4.html

But a quick summary is that a bloomery is a small chimney with alternating layers of pre-roasted iron ore and a lot of charcoal. Air is blown into the bottom through a small tube to ensure that the temperature is never too hot or too cold. Through a lot of complex chemical reactions, a lot of silicate and oxide impurities would filter out into slag and be separated from a more solid, but still spongy metal bloom.

The melting point of iron isn’t reached, however (that’s a technology for a future era), so the remaining solid bloom must be taken out and hit with a hammer. The impacts break away the more brittle and contaminated chunks of iron leaving behind the more usable material. After an excruciating process of reheating and hammering a bloom multiple times, we have some usable material for smithing (hopefully, as the attempt sometimes just flat out failed to yield a good product depending on circumstances–smelting was an art, not a science). Some of the slag waste product which still contained iron could be recycled with the next bloom to hopefully yield more iron.

Here is a quick video to help visual the process: iron smelting in bloomery furnace, extraction and compaction of iron bloom - YouTube

While you might notice from video, the workers have to destroy the bloomery to retrieve the bloom, more permanent and slightly larger brick versions did exist. As the centuries went by, people experimented with larger bloomeries. Overtime, very large waterwheel-powered bloomeries existed and even had their blooms lifted out from the top via crane. All of these are things to consider as we progress in-game from T1 to T4.

3). Metallurgical Charcoal

A key point to emphasize about iron smelting is that it was an art, rather than a science. Depending upon the impurities in the soil, the types of trees used for charcoal, the local quality of iron ore, the peculiar shape of the smelter, etc, the recipe to successfully smelt iron would be different. If you took a formula in one area and attempted it in another with locally sourced materials, it would likely fail. Master smelters would develop their own home-brew recipes that through trial and error that worked in their local areas.

Example of a recipe from an old-time German smelter: From the list above (see picture), for the best product, they determined they should mix iron ores taken from 3 locations. The ore should be a mixture of calcium-rich siderite and another special variety of siderite (likely containing some manganese impurities). The charcoal should be made from a mixture of Beech, Pine, and other common wood from the local area. Such a mixture, they found through painful trial and error, yielded a good result for their specific form and shape of a smelter.

One of the most important ingredients is charcoal. Now if you were to go out into your backyard and try to smelt copper or iron using barbecue charcoal bought from your local store, you will fail. The kind of off-the-shelf charcoal you can buy at your local supermarket is very different from the metallurgical charcoal you need to successfully smelt metals.

For the best results, you want a mixture of hardwood and softwood. Hardwood charcoal tends to be more dense, whereas softwood charcoal tends to be more reactive. Moreover, your charcoal mixture should be made from the branches of trees rather than the trunks of trees. For this special charcoal, the temperature of the kiln must be especially high and thus you only get a conversion process of 10-15% efficiency from wood to charcoal. What’s more is that you need many more times charcoal than iron ore for successful smelting. The density of charcoal is only about 200 kg/m3, whereas the density of iron ores are typically around 5,200 kg/m3. What you should realize is that most of your logistical burden consists mostly of charcoal by volume. For even a modest amount of iron, you’ll need many, many oxcarts of wood and charcoal just to support the operation of a modest smelter.

I must emphasize that the math adds up to some very hardcore deforestation for even a modest amount of industry. If you’ve watched farthest frontier’s intro about how “in the old-world, life has no chance of ever improving”, Europe did indeed have a deforestation crisis from the demands of heating homes and metalworking. This lack of available wood had a very negative impact on the quality of life for the average peasant and is a big reason why colonial America, even with its lack of infrastructure, had some of the highest standards of living for the lower classes.

But entire groves of “coppiced” woods were necessary to support metal industries. These ugly-looking forests would provide the more reactive branches in bulk necessary to support charcoal production for metallurgical furnaces.

In-game we ought to be able to do the same and grow such coppiced woods using our farm fields where every season, you harvest the branches off these fields of suitable trees. We should also maybe have a distinction between hardwood and softwood as well (the former taking a LONG time to grow). If we ever get shipbuilding as hinted in a recent stream about post-release plans, having hardwood already implemented might be a necessary precondition to ships.

4). Types of Iron Ore

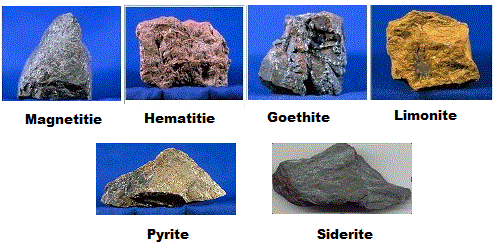

In-game we just have one generic “iron-ore” resource, but in reality it came in various types with differing grades of usefulness. The local quality of the iron ore on a generated game map might be a very good difficulty setting to take into consideration.

Important considerations for iron ore are how easily it decomposes into iron-oxide (FeO) or " Wüstite" as its known in mineral form. The other consideration is how likely the ore is to contain impurities like sulfur or phosphorous. Even just a fraction of a percent of these impurities can render iron unusable.

Magnetite (Lodestone) tends to be the richest iron ore with over 70% weight being iron. It already contains wüstite already being in the form FeO+Fe2O3.

Next up is Hematite (Red Iron Ore) with just shy of 70% weight being iron typically with the chemical form of Fe2O3 (which easily breaks down into FeO in a smelter).

Then there is Goethite (Brown Iron Ore) with just over 60% weight being iron typically with the chemical form of FeO(OH).

Finally there is Limonite (Yellow Iron ore) with only about half its weight being iron. With a chemical composition of FeO(OH) · n(H2O), much of its weight is actually water trapped in mineral form and tends to also contain unwanted impurities as a result.

Its easy to imagine a system where maps generate these ores and the volume yield/efficiency of mining and smelting depend on what local ore is available. We already have a similar system with farming/soil quality. But for a yield system, there are a few special cases to mention as follows:

Siderite (iron carbonate) has the chemical form FeCO3. While its composition is less than 50% iron by weight and doesn’t yield much iron as a result, its very easy to smelt because it easily decomposes into iron oxide (FeCO3 ⇒ FeO + CO2). It was often a favorite to mine in bulk.

Pyrite (Fools Gold) is a sulphite ore as opposed to the oxide ores mentioned above. Despite having the chemical composition, FeS2, by roasting it before placing in a bloomery, its possible to burn away the sulfur and introduce oxygen in its place. This is a thorough and painstaking process as any small amount of sulfur ruins the final product. While theoretically possible to smelt, people simply didn’t do it because of the economics involved (see above section about charcoal), and because Iron oxide ores were abundant anyways. But if you had no other options and were stubborn enough, it could be done in theory with great difficulty.

Finally, there is bog iron ore which is a very diluted form of Limonite or Goethite, but still played an important part in metallurgy.

In swampy terrain, certain types of bacteria tend to accumulate small bits of iron in gatherable clumps. For a lot of regions of Europe where no iron ore existed in notable quantities, bog iron ore was gathered painstaking by hand from peat soil, roasted carefully to remove impurities, and used for bloomery smelting. In-game, one might easily imagine a forager’s shack being able to collect bog iron ore from swampy terrain or peat bogs for a T1 or T2 settlement for early game use before proper mining infrastructure is established.

5). The other Metals.

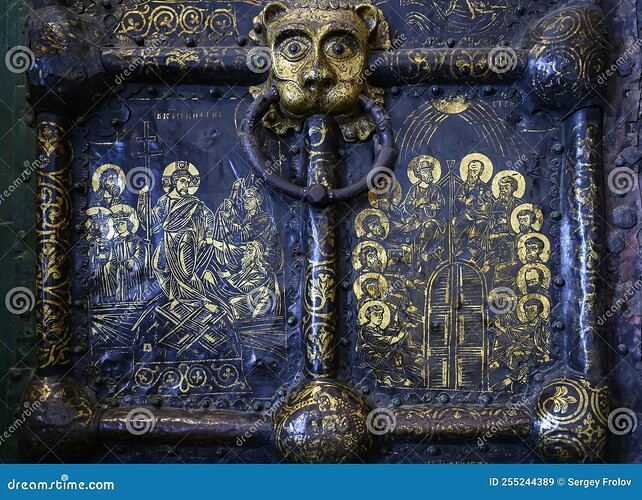

While we have a bloomery for smelting iron and a blacksmith for producing small wrought iron products like chain links, nails for construction, or the occasional spare tool or sword, the existing foundry should be repurposed for lead, copper, brass, and bronze products. Once again remember the difference between forged/wrought metal and casting a metal. The foundry would take wax (to make molds) and mass produce large pots, plating, etc or make larger objects like statues, church bells, or prestigious artifacts.

I would also suggest an additional building called “Tinkerer”, (note the etymology here: Tin-ker) that uses tin or pewter (an alloy of tin and lead) to make kitchenware like cups, plates, bowls.

While copper, tin, and bronze products are more easily mass-produced, the materials are a lot more expensive due to rarity. As a result, they were often diluted by lead. Instead of having a pure-bronze statue, you might have a much cheaper “plastic bronze” statue which used a mixture of lead and bronze. Lead in this case would be a way to make cheaper mass-produced metal products by combining it with other stronger castable materials. Lead’s other primary use would be the cupellation process which is important for silver and gold mining.

Native gold and silver tend to be extremely rare. What impure ores that did exist often were combined with molten lead. When melted, the lead oxide would bond with impurities and melt at a lower temperature, leaving behind the valuable precious metals.

Mercury can also extract gold by amalgamation from running rivers. In some rare cases it had genuine medicinal uses (with often equally bad side-effects, but sometimes you’re that desperate). But its most distinct use in-game would be for gilding objects with gold and silver. Such fire-gilding might be used to raise the luxury value of furniture, kitchenware, pottery, weapons, armor, or even religious artifacts.

6). Small bonus section: preserving wood

A small detour away from metal to talk about construction: Beyond hardwood, softwood, maybe needing nails for timber constructions, we should maybe need to preserve wood as well. We already have flax in-game which can be ground at a mill to make linseed oil. Linseed oil in turn can be used to preserve wood to prevent it from rotting away, can be used as a binding agent for painting, or even find use as a lubricant for machinery. There is a bit of a cross-over with metallurgy here as linseed oil was often mixed with lead oxide to ensure a long-lasting product.

Much of this post assumes we’re trying to represent late 13th, 14th, or early 15th century technology, but as we progress a few centuries after, metalworking become a lot more advanced with new techniques, processing, and materials. Pig iron, finery hearths, consistent steel-making (cementation process and shear-steel), the patio process for using mercury in silver mining, among many other innovations occur. Would be happy to go into detail too, but that’s for another post. But for now, I think a lot of the things mentioned above would be applicable to adding some variety to industry in-game.

Thoughts?